Cold, hard truth from a middle school boy that explains why many people want to succeed but few do.

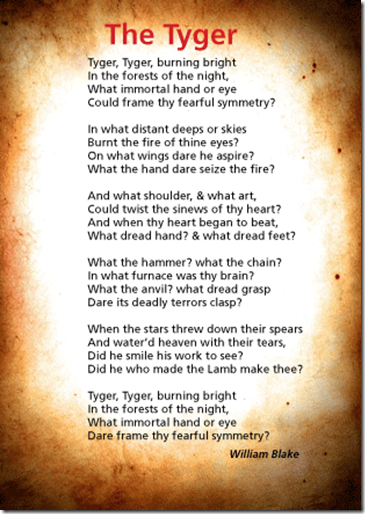

/A middle school student reading a poem onstage at a TEDx Talk said this:

"You are who you want to be."

This is some cold, hard truth.

That is a truth that many people don't understand.

That is the truth that holds many, many people back from achieving their goals.

What does it mean?

I am often contacted by people (more often than you might think) who want my advice on becoming more productive. More efficient. A better writer. A published writer. A better storyteller. A better teacher. They want to be more organized. More goal oriented. Happier. Healthier. More successful.

Sometimes I am able to help. I'll coach them. Point them in the right direction. Offer some advice. But what I have learned over the years is this:

You are who you want to be.

Many people want to improve their life.

Few people want to change in order to do so.

People assume that I have some magic bullet to offer that will instantly make them more successful. They think that all they are missing is a bit of unfound wisdom. A simple strategy or two that will change everything. A mindset that will transform them into the person they've always wanted to be.

They want the results, but they don't want to do the work required to achieve those results.

When my doctor told me that my cholesterol was borderline and suggested that I start eating high fiber foods like oatmeal, I began eating oatmeal every single day for lunch, almost without exception.

When I returned for my annual physical a year later, my cholesterol was down almost 40 points. My doctor was shocked. She was sure that I was going to have to begin taking medication. When she asked me what I had done to lower my cholesterol, I told her:

"Oatmeal. I eat it every day. Just like you told me to do."

Most people want to lower their cholesterol naturally and avoid a lifetime of medication, but few are willing to take the steps to make it happen, so they end up taking pills for the rest of their life.

You are who you want to be.

I wanted to be someone who didn't have to take medication to control his cholesterol.

Most people don't want to take medication to control their cholesterol, but they want to maintain their current diet and exercise regime more.

In the end, they are people who eat the foods they like most and wish their cholesterol was lower.

They are the people they want to be.

This doesn't mean that change isn't possible. It simply means that you need to want to change more than you want to remain the same, and for many people, this is not the case.

I don't know if that kid onstage understood all this when he spoke those seven words, but he was right.

You are who you want to be.