I performed stand up comedy for the first time for one very important reason.

/Last year, a friend asked me to try stand up comedy with him.

I said no and moved on with my life.

But knowing I had to follow my "Say yes to everything" philosophy, I called him back the next day and said, "Fine, I'll do it, but I won't like it."

We agreed that in addition to performing comedy, I wasn't allowed to simply tell a funny story. I have plenty of stories that could fill the five minute requirement and make people laugh throughout, but this had to be different. I had to tell jokes. Not stories.

I thought this was fair, but I was also terrified.

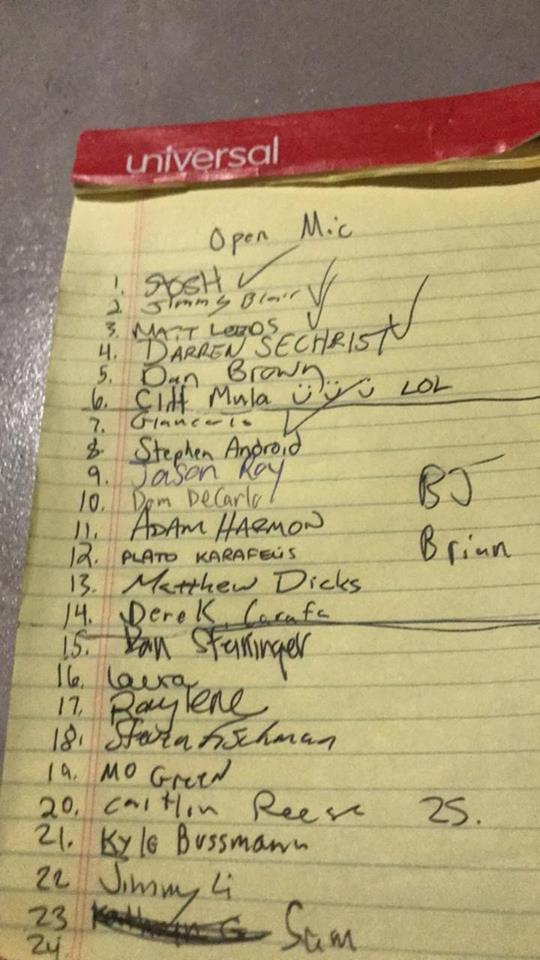

Almost a year to the day after declaring my intent, I took the stage on Monday night at Sea Tea Improv in downtown Hartford to perform stand up comedy for the first time.

It went well. I was not fantastic. I performed for the requisite five minutes, telling jokes about parenting, marriage, Jewish food, and sex. People laughed. A few people complimented my performance afterwards, and a couple more found me online the next day to offer positive feedback.

Most important, Elysha thought I was funny, and a couple friends in the audience were supportive as well.

A friend (but not the friend who challenged me to comedy in the first place) also took the stage on Monday and performed. He did well, too. As he pointed out later, some of the comics were asked by the host if it was their first time doing comedy.

Neither he nor I were asked that question. We were at least good enough not appear new.

But it was a strange experience, too. I took the stage without any real plan. I had a couple opening sentences which I knew I could use to launch me into a riff on the realities of being a father, but after that, I was winging it. I said funny things that came to mind, but immediately after saying them, I knew that there was an even funnier way to say them.

And I wasn't telling stories. I was telling jokes. Trying to make people laugh with words instead of story.

And for the first time in a very long time, I felt nervous as I took the stage. Those nerves evaporated after I began speaking, but for a few moments, I felt the nerves that so many of my storytelling students feel just before taking the stage.

I'll try stand up comedy again. I'll keep a running list of possible funny ideas as they occur to me, and when I think I have five minutes worth of material, I will prepare another set and give it a shot. Perhaps I'll take the five minutes that I did on Monday to another club as well. A producer at a comedy club in Manhattan has asked me to do 20 minutes at her club, and I could definitely stretch the 5 minutes that I did on Monday to a much longer set if I wanted.

But here is the important part about Monday night:

I tried something that was new, frightening, and hard. That is why I did it. Complacency is tragic. Monotony is death. The absence of new horizons is an unfulfilled, wasted life.

I cannot stress this enough: You must find and try things that are new, frightening, and hard. This is the elixir of youth. Days filled with excitement and anticipation. A life absent of regret.

As a child, my life was filled with things that fit all three of these categories. I took new classes in new subjects every semester. Played new sports. Changed schools. Learned to drive. Asked girls to dance. Hiked up new mountains. Swam in new ponds. Made new friends. Played new musical instruments. Learned to speak a new language. Had sex for the first time. Earned my first paycheck.

A young person's life is inextricably filled with things that are new, frightening, and hard. As we get older and experiences begin to pile up, those opportunities become fewer and farther between. People settle into routines. They establish patterns. Their zeal for risk taking wanes.

Before long, they cannot imagine trying something new, frightening, and hard. They become set in their ways. They plod through life. They can't imagine staying up all night or driving to some faraway place on a whim or otherwise disturbing their routines.

They are getting older while getting old.

I say yes to everything because I don't want to get old as I get old. I want the promise of days that are new and frightening and hard. I want to know that what I know now will not be all that I ever know.

I cannot recommend the new, frightening, and hard enough. Stay young before you get old.