Sequel Protection Service: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

/So many times in my life, I’ve wished that I had avoided one or more of the sequels to a book or movie. Spoiling the beauty of an original story with a disappointing or (even worse) destructive sequel is a tragedy that should befall no human being.

Thus behold:

Matthew Dicks’ Sequel Protection Service.

Having suffered through scores of horrendous and damaging sequels, I have thrust the mantle of Sequel Protection Champion upon myself in order to spare future consumers the pain that so many of us have experienced.

I will tell you which sequels are worthy of reading or viewing and which should never be seen.

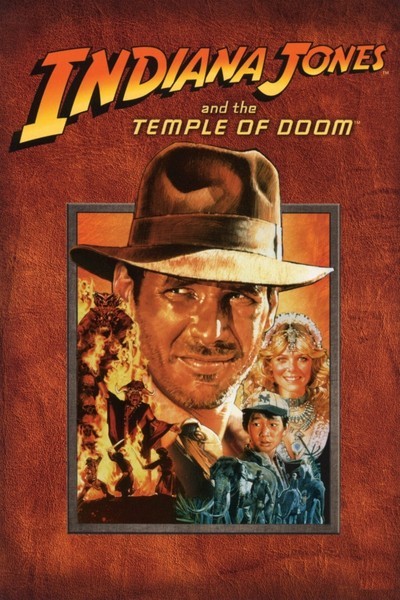

Today’s subject: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Warning: I will be spoiling this film with the expectation that you will never watch it.

Part of the trouble with this film is that it comes on the heels of one of the greatest movies of all time: Raiders of the Lost Ark. It would seem impossible to successfully follow a film of this caliber, and yet the franchise manages an equally impressive film with its third installment: Indiana Jones and the Final Crusade.

The Temple of Doom is a mess of a movie. I will outline three primary complaints, but there are more than enough for you to avoid this movie at all costs, even if these three reasons don't strike you as compelling.

1. The movie is unrealistically unrealistic. In fiction, it's said that you get one coincidence. One chance encounter. One unbelievably fortuitous (or disastrous) unlikelihood. This same rule applies to the magic in the Indiana Jones franchise.

You get one.

In the first film, the moment of "magic" comes at the end, when the Ark of the Covenant is opened, revealing its power.

In the third film, the magic also comes at the end in the form of the Holy Grail and the knight protecting it. In these two films, it's the magic that is sought, so the film is realistic until the quest is complete.

The Temple of Doom is riddled with magic:

- A potion that turns Jones into a bad guy (and children into zombie slaves).

- The ability to remove the beating heart from a man's body and then seal the wound, all with an outstretched palm.

- Magical stones that react to incantations and would allow the possessor to rule the world.

The quest is not for a mythical or magical artifact. Instead, the movie centers on Indy's battle against the magic being used to enslave children. This makes it a very different, and in comparison to Raiders of the Lost Ark, a very silly film.

2. Indiana Jones is not the man we know and love in the first and third films.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark and Final Crusade, we meet an archaeologist who accepts a mission to preserve an ancient artifact and keep its powers out of the hands of evil men and women. In The Temple of Doom, Indy is initially motivated by greed. He desires the magical stones in the temple because he believes that they will bring him fame and glory.

This is not the Indiana Jones who we root for in the other two films.

The Temple of Doom is also prequel to Raider of the Lost Ark, and all of the magic in this movie destroys the continuity of the franchise and undermines Indy's character as its presented in the first and third film. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, for example, Indy rejects the supernatural, calling it "all that supernatural hocus pocus." Yet this prequel clearly establishes Indy's exposure to magic and the supernatural in a profound way, making his hocus pocus dismissal ridiculous.

3. The female lead in The Temple of Doom is weak, ineffective, and constantly screams for help.

The female lead in Raiders of the Lost Ark is nearly as tough as Indy. She takes action on her own accord, saves Indy's life more than once, and is a fairly well developed character.

In the third film, the female lead turns out to be a villain who is both brilliant and dangerous and complex.

In The Temple of Doom, we meet nightclub singer Willie Scott, who is primarily a damsel in distress throughout the film. She cries for help, screams in terror, and is generally a pathetic character.