I was speaking to some of my former storytelling students - children of Holocaust survivors who had gone through a workshop series with me that culminated in a storytelling performance.

One of them told me, "Now I see stories everywhere. Everything is a story."

While I don't agree that everything is a story, I knew exactly what she meant. Our lives are filled with storyworthy moments. More than you would ever imagine. Those who mine their lives for these moments and develop them into a treasure-trove of stories constantly add depth and breadth to our lives and their own.

We are the ones who remember our lives best. We remember our lives through story.

But possessing so many stories has an added value. When you have a lot of stories, you have the potential to inspire, amuse, entertain, or change minds, regardless of circumstances. No matter the context or need, you'll always have something to say.

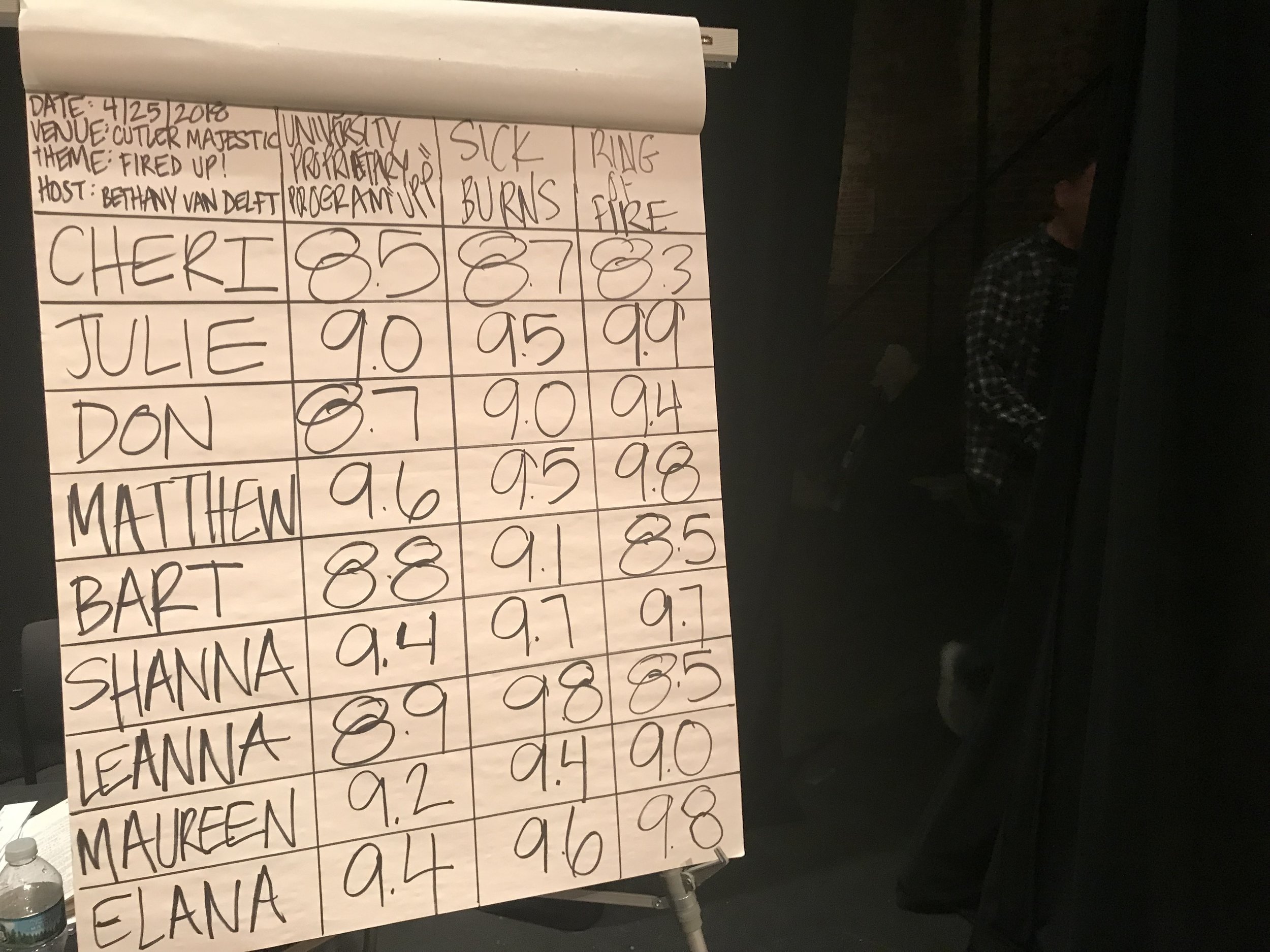

A couple years ago, I was in Indiana, speaking and performing at a variety of events at college campuses in and around Purdue University. I spoke about storytelling, writing, and personal productivity, and I produced and hosted a story slam for students.

A large conference on human trafficking was also underway on campus. I was asked if I'd be willing to close the conference with a speech to the attendees.

I agreed.

Two weeks before the speech, one of the organizers called and asked about my expertise in human trafficking.

"I have none," I said,

I'll never forget what he said:

"I guess that's what Google is for?" he said nervously. "Right?"

Wrong.

It turns out that when you have a treasure-trove of stories, you can speak to almost any audience regardless of the topic, purpose, or need.

Besides, after three days of speeches, breakout groups, and seminars on the topic of human trafficking, did his audience really want one more speech on human trafficking from a guy who had to conduct a Google search on the subject?

Instead, I told a funny story about how I helped a shy student emerge from her shell after years of withdrawal, and in doing so, I came to realize that although I had "saved" this one girl, there were many other shy, silent children who I had not, primarily because I had stopped trying. I had given up on them. I had presumed that someone else would come along and fix their problem.

Once the story was finished, I explained that when engaged in important work like teaching or seeking to end human trafficking - people work - we can never give up. We can never quit. We cannot assume that someone else will solve the problems.

More importantly, we can't afford to act slowly. We are not making widgets or selling keepsakes. The quality of a human being's life is in our hands. The very last thing we can do is allow bureaucrats, politicians, and ineffective administrators tell us that meaningful change takes time. Institutional transition can't happen overnight. We can't allow ineffective leaders to tell us that large ships don't change their direction overnight.

This might be fine if you're selling real estate, building furniture, or coding an app, but when you're dealing with the lives of human beings, these passive, placating statements cannot be allowed to stand.

As a teacher, I cannot be slow to action when a child's future is at stake. I cannot stop trying to save a child simply because every tool in my belt has failed.

Like me, the people who work to end human trafficking cannot afford to move slowly. Cannot waste a moment of time. The people of the world who choose to make a career out of saving lives must be the fastest, hardest, most dedicated people possible. They must be red tape destroyers. Bureaucratic assassin. Fast moving missiles of good.

I knew nothing about human trafficking except that it was too important to not work like hell to bring it to an end. Happily, I had a story that applied similarly and was filled with stakes, humor, and heart.

It went over very well. The organizer called me the following week to tell me that it was the only time all week that anyone laughed and that my message was heard loud and clear by conference attendees:

We are human saving warriors. We must move at lightning speed. We cannot allow anyone to stand in our way or even slow us down. Human lives are at stake.

If you are a person with a treasure trove of stories, you can speak anywhere about just about anything. It's hard for me to imagine someone calling tomorrow and asking me to speak on a topic that I couldn't find an entertaining, enlightening story and associated message that would work.

Want to become a person full of stories? I recommend Homework for Life: