Verbal Sparring: If you don't like it, leave.

/A reader contacted me yesterday, asking me to reprint a post I wrote back on September 26, 2016 entitled “Verbal Sparring: If you don’t like it, leave.”

I had no recollection of the post, which didn’t surprise me. When you write a post every single day of your life since the spring of 2005, you write a lot. 3,905 posts on this blog alone, plus another 1,000 or so on my two now-defunct blogs.

That’s a lot of thoughts, ideas, stories, and observations.

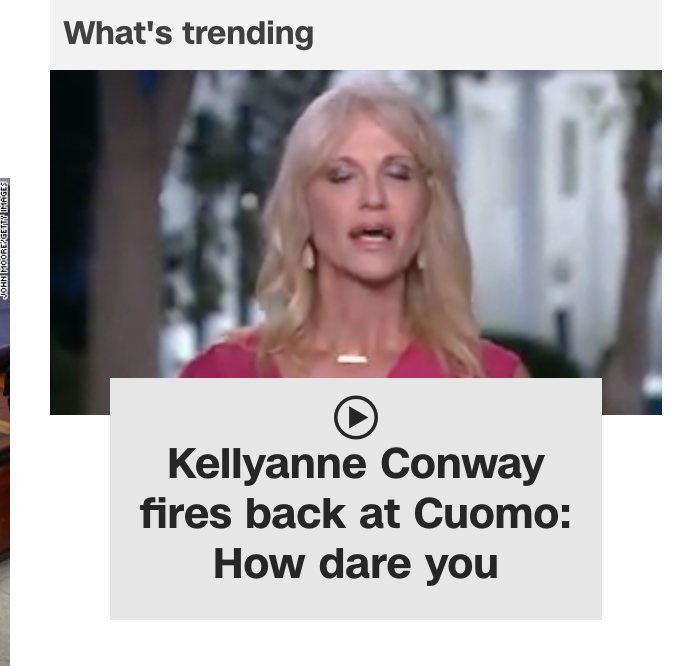

But it appears that I was very prescient back in 2016 in writing about a topic that has suddenly taken center stage in the national consciousness.

So here it is:

A post lightly edited from 2016 in my Verbal Sparring series offering advice in the event a racist imbecile like Donald Trump tells you tells you that your dissent of the status quo - the very foundation of our country - is an indication that you cannot love your country and should be reason enough for you to leave.

It's such a stupid argument, but it's one often used by racists against people of color and by other morons in a variety of contexts, so when it arises, it needs to be beaten back.

Here's how.

_______________________________________________

"If you don't like it, leave," in all its variations, is a coward's argument. It's an argument made by people who are afraid of debate, don't understand logic, and want to escape the fray as quickly as possible.

"If you don't like, leave," implies that arguing for change is not permissible.

"If you don't like, leave," implies that dissent is unwarranted.

"If you don't like, leave," implies that diversity of mind is out of bounds.

There are many responses to this ridiculous argument and arguments like it. I’ve broken them down into four basic categories:

Refuse: "No, I'm not going to leave. You don’t actually have any power over my where I choose to live or work or even stand. I’m going nowhere. Instead, I'm going to fight."

Make the logical argument: "Telling me to leave implies that dissent and change are not permissible here. That is nonsense, of course. Change is constant, and it only comes through a diversity of opinions. This is not North Korea."

NOTE: This argument does not work in North Korea.

Attack: "It sounds like you're afraid of debate. Maybe your ideas suck and you know it. Maybe I intimidate you. Maybe you know that you're standing on shaky ground. Maybe you’re afraid of me. Yes, that’s probably it. I scare you. Either way, I'm not taking my toys and going home because I'm not afraid of a good argument and a weak-willed sap like yourself."

Historical: "If that was an actual argument, then it would stand to reason that anytime someone was not happy with a policy or position, they should leave. Women don't like receiving 70 cents on the dollar? Leave. African Americans don't like separate but equal? Leave. A soldier doesn't like a general's decision? Leave. That's just stupid. It's not how the world actually works outside of your stupid head."

I tend to favor the attack strategy, but that may just be my nature.