Why a poached egg is funny

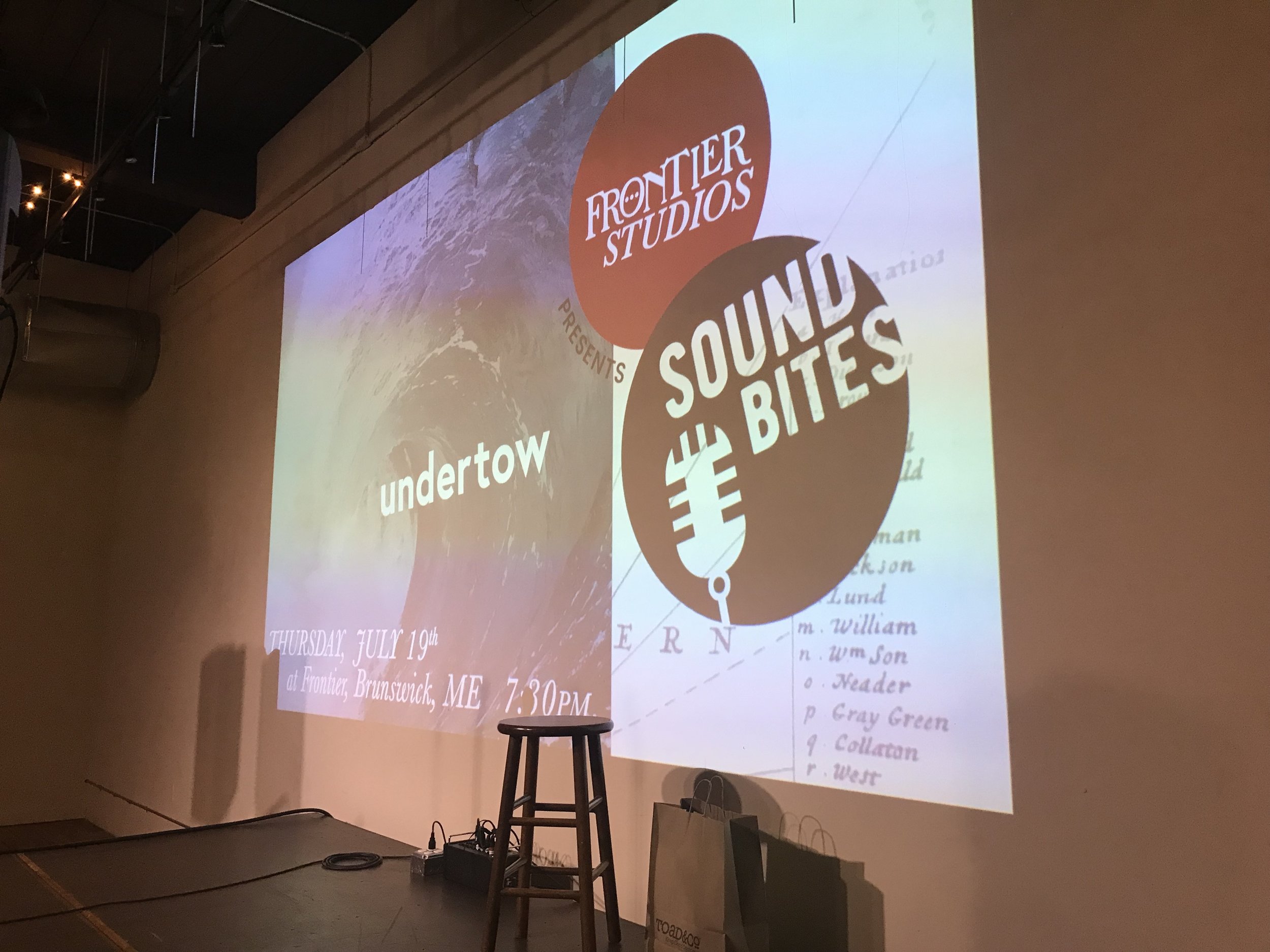

/I performed in a show in Maine earlier this week called Sound Bites. In addition to telling a story, I also served as the emcee for the evening, introducing storytellers and bantering a bit between stories.

Doing my best Elysha Dicks impression.

During one of the stories, a storyteller talked about how she can't cook a poached egg. When her story was done, I took the stage and told the storyteller that not only could I not cook a poached egg, but I don't actually know what a poached egg is, which is sadly true.

The audience roared with laughter.

Later on, I asked myself why.

Why was that funny? I knew it would be funny, and I knew if I delivered it well, it would be really funny, but why?

I've become a little obsessed with humor recently. Doing standup and constantly being asked in workshops to assist storytellers with being funny, I've become interested in looking closely at what makes things funny.

Here's what I think about my poached egg joke:

I think it's funny because it's a moment of surprising vulnerability. I think it was a combination of unbridled honesty, uncommon authenticity, and a willingness to speak about something that most would not.

Yes, it's also a self-deprecating comment, which is often funny, but I think it's more than that.

In that moment, most people don't admit to not knowing what a poached egg is. It's not some rare Tibetan cuisine or a fruit that only grows in the South Seas. It's a poached egg. I've heard about poached eggs all my life, as have most people, and yet I have no idea what that is. Most people would worry about sounding foolish or naive or even dumb to admit this, especially when standing before more than 100 people. When I acknowledge this surprising truth, they laugh. But they don't laugh at me. They laugh at my unexpected vulnerability.

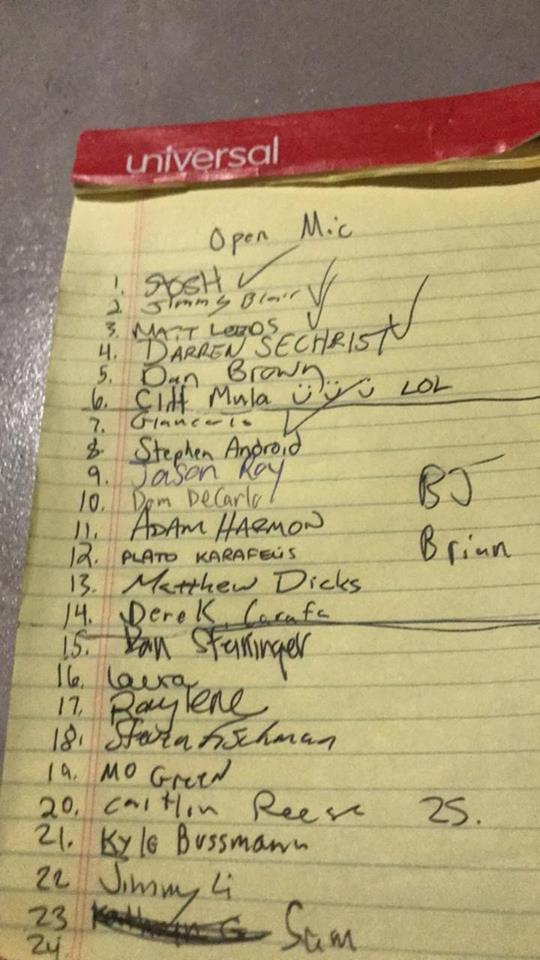

I see this at comedy open mics all the time. A comedian is bombing, but with a minute to go in his set, he says something like, "I didn't realize how silent not laughing can be" or "Thank God I don't have any friends to invite to these disasters" and the audience (mostly comics themselves) roar with laughter. Sometimes they don't even say these comments to the audience. They are speaking almost under their breaths to themselves.

Yet it's the funniest moment in their set.

Unplanned moments of vulnerability. Unexpected peeks into a comedian's soul.

Yes, the content is also amusing, and their facility with language is strong, but it's when the comedian drops his guard, ceases his schtick, and stops cracking jokes when we laugh.

This is why people laughed at my poached egg comment. I was shockingly vulnerable. I said something that most don't say. I spoke to a place in the hearts of the audience where they hide their own shame. Their own poached egg ignorances. I opened that door and let in a little light. Made them feel a little less foolish. Perhaps even a little happier with their own state of being.

Most important, I made them laugh.

It's not funny that I can't identify a poached egg. It's funny when I tell you that I can't identify a poached egg.

There's a lot more I could say about comedy, and there is a mountain for me to still learn, but this I know is true:

The best comedians speak the truth. When they say something like, "I was talking to my girlfriend the other night..." they were really talking to their girlfriend the other night. Not the girlfriend of a friend whose story they heard five years ago but have taken on as their own because it's funny.

They are speaking the truth. Because of this, they have the opportunity to be vulnerable with the audience. Surprisingly, so. With that vulnerability comes the opportunity for a laugh. A big one. A memorable one. One that might even touch the hearts of their audiences, too.

I love storytelling because I am afforded an opportunity to speak my truth, and when that truth is unfortunate, embarrassing, shameful, or disastrous, even better. People want this. They crave the failures and disappointments. They want to hear about our epic disasters and moments of awkwardness and shame.

Finding someone to brag about themselves in this world is not hard. Finding someone who is willing to tell on themselves is much harder to find. This is why people are drawn to the art and craft of storytelling.

It's honest, authentic, and vulnerable.

The more unfortunate the moment, the more vulnerability required to tell it.

Admitting that you have no idea what a poached egg is in front of an audience of 100 people is an act of vulnerability.

It's also funny. For that very reason, I think.