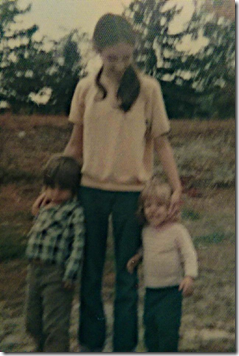

My aunts and uncles were once young and strong and infinite. This is how I try to remember them even when the shadows of my ongoing existential crisis creep in.

/I’ve been thinking about my grandparents a lot lately. Specifically, I’ve been thinking about the families that they raised and what life must’ve been like back then. In the not-so-old days.

I have an interesting family dynamic:

My mother married my father.

My mother’s brother married my father’s sister.

Two families more closely intertwined by marriage than most. And large families, too.

My father was one of seven children.

My mother was one of six.

Until my mother and father divorced when I was about eight years-old, Dad lived in my childhood home, next door to his father, my grandfather. Dad’s grandfather (my great grandfather) and his uncle (my great uncle) lived there as well. For much of his life, his brother (my Uncle Neil) lived there, too.

Two houses down from our home lived my father’s brother, Harold, and his wife, Cathy. Half a mile down the road lived my father’s youngest sister, Sheila, and her husband, Tim. Across the street from our house and across the street from my grandfather’s house were the homes of my uncle’s wife’s family.

Our street was a bit of a family compound.

The rest of the family, on both my mother’s and my father’s side, lived nearby. Both sets of grandparents lived in my hometown, as did most of the uncles and aunts. Until my mother’s sister, my Aunt Paulette, moved to South Carolina when I was young, every aunt and uncle with the exception of one lived within fifteen minutes of my home.

Today, the families are much smaller.

All of my grandparents are dead.

My mother and her older sister are dead.

Two of my father’s brothers and one of his sisters are dead.

Thirteen children amongst the two families now reduced to eight.

But I like to think back to a time, prior to 1978, when things were different. My father’s mother had died a few years earlier, but otherwise, the family was complete. It was a time when all thirteen of these children were alive and well. Some were married and some were single, but none had been divorced yet. The families were intact. For a tiny sliver of time, things were as they should be. There were no shadows at the family picnics.

My Aunt Carol, my mother’s oldest sister, passed away first, following her husband, my Uncle Norman, who died a little less than decade earlier.

My parents divorced. My father left the house and farm that stood in the shadow of his childhood home. He went from living next door to his father to living alone in an apartment behind a liquor store.

Then my Aunt Sheila died tragically in a doctor’s office while receiving an allergy shot. She was still in her twenties and the mother of three.

My Uncle Neil died years later, followed by my Uncle Harold just recently. More divorces along the way. More families chopped in half. Reconstituted. Chopped again.

But I like to think about my grandparents and pre-1978: a time when all of their children were alive and well. When their marriages were intact and futures were bright. When death had not yet begun to cast its shadow across the landscape of the family and whittle it down, piece by piece.

It must have been a lovely time for my grandparents. A lovely moment, really. A few years in the sun before things began to crack.

It must be hard to watch a family fracture. Separate. Shrink.

A not-so-long time ago, thirteen children who would one day become my aunts and uncles lived in the tiny town of Blackstone, MA. They ran and played and laughed and grew. They found work. They fell in love. The sun was warm on their backs and the grass was soft underfoot.

I like to think about them like this. Young and strong and infinite.

Now there are shadows where loved ones once stood. Aging bodies and broken hearts and lost love. Someday thirteen will become zero, and those once glorious and indestructible children will be no more.

One hundred years from now, they will be all but forgotten. Names occasionally uttered in discussions of family trees. Mentioned in soon-to-be-forgotten family stories. Etched into tombstones no longer visited.

I would – if I could – reach back into time and tell those thirteen children, spread amongst two families, to hold onto their youth with every ounce of strength that they have. Cherish it. Grab onto one another and hold tight.

And I would tell them to run. Run fast and hard and with reckless abandon through fields and streets and wood because some day running will be a thing of the past. I would urge them to run from those shadows that are looming closer each day and remember their time in the sun, because it is all too fleeting, and someday, thirteen will become none.