Got kids? Here's how to turn them into writers.

/As a teacher and a writer, I often give parents advice on helping their children to become effective writers who (more importantly) love to write.

My advice is simple:

Be the best audience possible for your child’s work. If he or she wants to read something to you, drop everything. Allow the chicken to burn in the frying pan. Allow the phone to ring off the hook. Give your child your full and complete attention. When a child reads something that they have written to someone who they love and respect, it is the most important thing happening in the world at that moment. Treat is as such.

Don’t look at the piece. Don’t even touch the piece. Any comment made about the piece should never be about handwriting, spelling, punctuation, and the like. By never seeing the actual text, you innate, insatiable parental need to comment on these things will be properly stifled. Your child does not want to hear about your thoughts on punctuation or the neatness of their printing. No writer does. Your child has given birth to something from the heart and mind. Treat it with reverence. Speak about how it makes you feel. Rave about the ideas and images. Talk about the word choices that you loved. Compliment the title. Ask for more. Forget the rest.

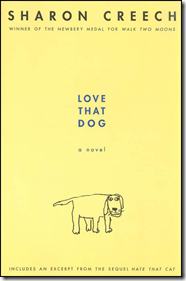

Remember: Rough drafts are supposed to be rough. Even final drafts are not meant to be perfect. That’s why editors exist. Go online and look at the rough drafts of EB White’s Charlotte’s Web. They’re almost illegible. Who cares? Writing is messy.

Once your child has finished reading the piece, offer three positive statements about the writing. Compliments. Nothing more. Only after you have said three positive things may you offer a suggestion. Maintain this 3:1 compliment/criticism ratio always. Use the word “could” instead of “should” when commenting.

If your child asks how to spell a word, spell it. Sending a child to the dictionary to find the spelling of a word is an act of cruelty and a surefire way to make writing less fun. You probably so this because it was the way that your parents and teachers treated you, but it didn’t help you one bit. It only turned writing into a chore. If you were to ask a colleague how to spell a word, you wouldn’t expect to be sent to the dictionary. That would be rude, The same holds true for your child.

Also, the dictionary was not designed for this purpose. It’s an alphabetical list of definitions and other information about words, but is wasn’t meant for spelling. Just watch a first grader look for the word “phone” in the F section of the dictionary and you will quickly realize how inefficient and pointless this process is.

When it comes to writing, the most important job for parents and teachers is to ensure that kids learn to love to write. If a child enjoys putting words on a page, even if those words are poorly spelled, slightly illegible, and not entirely comprehensible, that’s okay. The skills and strategies for effective writing will come in time, though direct instruction, lots of practice, and a little osmosis. The challenge – the mountain to climb – is getting a child to love writing. Make that your primary objective. Make that your only objective. Do everything you can to ensure that your child loves the writing process. Once you and your child achieve that summit, the rest will fall into place.

I promise.

Except for the handwriting. Sometimes there’s nothing we can do about that. Just be grateful that we live in a world where most of the writing is done on a computer.