School lunch shaming needs to stop. Simple solution: Adults need to stop acting despicable.

/As a kid who received free breakfast and lunch for his entire childhood, I am keenly aware of the stigma, embarrassment, and shame associated with not having enough money to feed yourself.

As a child, teachers took the daily lunch count by asking us to raise our hand if we were:

Buying hot lunch

Buying cold lunch

Getting free hot lunch

Getting free cold lunch

Just writing those words brings me right back to the shame and embarrassment that every morning held for me.

Later on, when I was homeless as an adult, I never looked into the possibility of soup kitchens or other programs to feed the homeless for the very same reasons:

I'd rather be hungry than humiliated.

I had thought that the system of requiring kids to raise their hands to indicate their economic status was a thing of the past. I assumed that it was a careless, thoughtless process that teachers and other school officials eventually recognized as wrongheaded and insensitive.

Then I read about the food shaming that is currently going on in schools around the country.

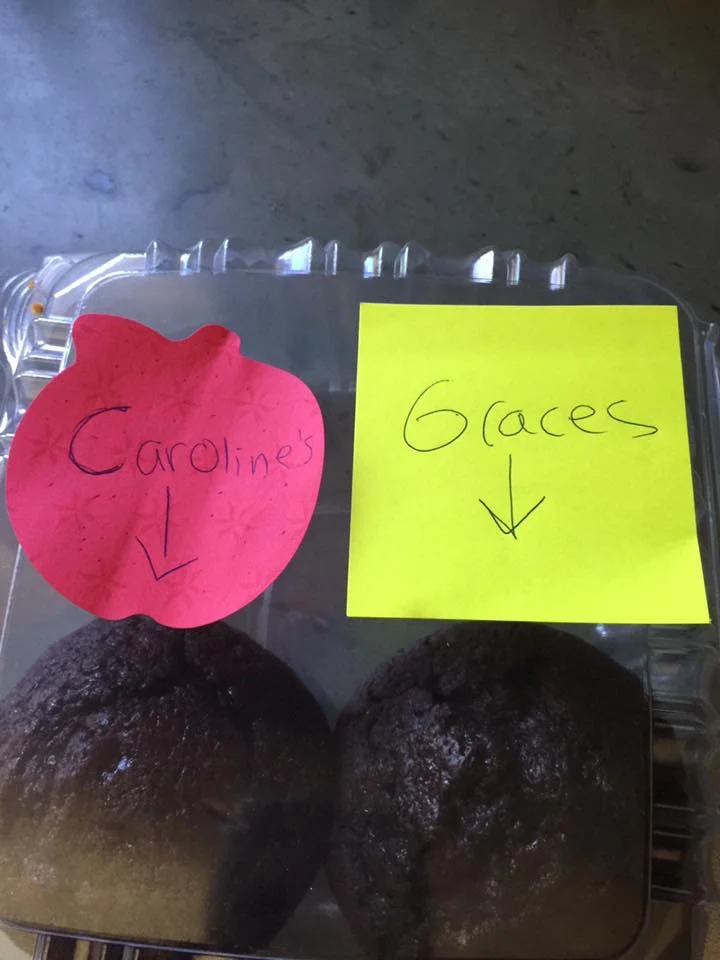

"In Alabama, a child short on funds was stamped on the arm with “I Need Lunch Money.” In some schools, children are forced to clean cafeteria tables in front of their peers to pay the debt. Other schools require cafeteria workers to take a child’s hot food and throw it in the trash if he doesn’t have the money to pay for it."

In other towns, children were made to wear a wrist band or perform chores in exchange for a meal. Oftentimes an alternative meal is provided when a child is short on funds, signaling their family's financial difficulties to the rest of the student body.

It's disgusting. Worse, these policies are being enacted by adults who have been trusted to teach and protect children. How can any adult with even a shred of decency do this to kids?

I suspect that the reasons are many.

Stupidity

Expediency

Callousness

The desire for profits (school cafeterias are often separate businesses run inside the school)

But I suspect the most common reason for this food shaming is an absence of empathy. A failure to understand the stigma and shame associated with being poor. A lack of contact with people in a different socioeconomic class.

Recently, I was debating a point with my cohost on our podcast, Boy vs. Girl, when she argued that my experiences with poverty (the removal of all parental support at the age of 18, my struggles with poverty and hunger, and my eventual homelessness) were not normal.

I pushed back - perhaps not hard enough - on this idea. While hunger, homelessness, and poverty may be unusual experiences for people in the socioeconomic circles that I now occupy, these conditions are unusual at all for people in a lower socioeconomic classes. Food insecurity, lapses in adequate housing, and even homelessness are not uncommon. When I was poor, I knew many people who spent months and even years couch surfing, squatting, living in cars, living in tents, and trapped in the eviction cycle.

I had family members who were homeless for a time.

I think it's easy to forget about these people when we don't see them everyday. It's easy to underestimate their numbers when they don't occupy our social circles. It's especially easy to forget about them when they try like hell to disguise their poverty in an effort to preserve their dignity, as so many do.

As I did.

48 million Americans - including 13 million children - live in households that lack the means to get enough nutritious food on a regular basis. As a result, they struggle with hunger at some time during the year.

These people exist. They exist in large numbers.

It's hard enough to be poor. It's terrible to be hungry as a child. The last thing these kids need is their school highlighting their poverty with these despicable, stupid, insensitive acts of cruelty.

Adults should know better.

Earlier this month, New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez signed the Hunger-Free Students’ Bill of Rights, which directs schools to work with parents to pay their debts or sign up for federal meal assistance and puts an end to practices meant to embarrass children.

I was happy to see a state taking action against these terrible practices, but I was also saddened to learn that action was required.

Even if you've never experienced poverty, and even if you don't know someone who is impoverished personally, it doesn't make much effort or imagination to understand how traumatic food shaming can be for a child.

So use some effort and imagination, damn it. Stop embarrassing yourself and humanity. Don't be a despicable, disgusting adult.