Q. My third grade son recently came home in tears saying he didn’t want to go to school anymore because he was punished for talking during silent reading. The teacher kept him in from recess. I think this is horrible. It isn’t a teacher’s job to destroy a child’s love for school. Instead of constant punishment for every little infraction, what about using positive reinforcement?

I was asked by a friend to offer an answer to this question. I have a few thoughts:

1. A good teacher will acknowledge and honor the feelings of the parent in this case. As a parent myself, I would also be saddened and concerned if my child came home from school in tears declaring he didn't want to school anymore. This is not something that we should want for any child, and I would likely be just as upset as this parent.

2. We must also acknowledge that this was not the teacher's desired outcome. To think otherwise makes no sense. So yes, the parent is correct when she says that it isn't a teacher's job to destroy a child's love for school, but the teacher knows this already. It wasn't her intention. Assuming otherwise is an emotional response and not useful to solving this problem.

Stating the obvious is never a reasonable argument.

We must also acknowledge that children say things during emotionally charged moments that they don't necessarily mean, and they often cry in response to varying levels of disappointment. This child's declaration that he doesn't want to return to school is a common refrain made by many kids over the course of their academic career. The child may believe this in the moment but will not feel this way in the long run. When a child says, "I hate you!" to a parent, we know that this is likely a statement made in anger with no real meaning. A similar dynamic may be playing out here.

I taught third grade for ten years. A third grader's statements are not exactly measured and considered.

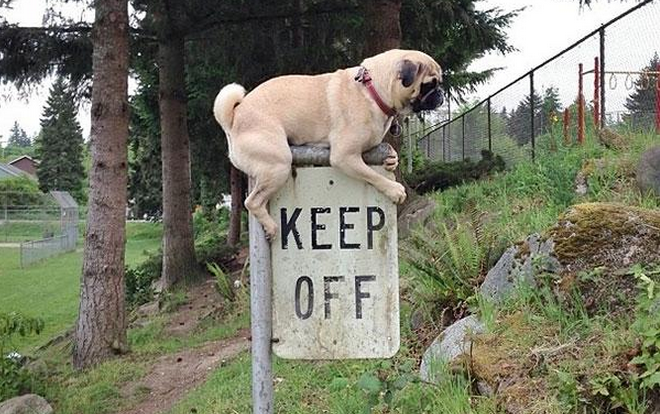

3. The parent is also correct that "constant punishment for every little infraction" is not appropriate. But I have no evidence of that here. She is pointing to a single infraction and a single punishment. So I'm hesitant to assume how often infractions are being punished in this classroom.

4. The parent is also correct that positive reinforcement is also effective, but she also is not clear about the amount of positive reinforcement being used in the classroom. Am I to think that this teacher uses no positive reinforcement (which is very unlikely)? Or is the parent proposing that in this particular instance, positive reinforcement would have been more effective than a punishment?

I can't tell.

5. Parents must also acknowledge that children are not reliable witnesses to the actions taking place in a classroom. They lack objectivity, perspective, and the background knowledge needed to accurate report events and glean nuance. I used to work with a kindergarten teacher who would tell parents, "I'll only believe half of what they tell me about you if you agree to only believe half of what they tell you about me." The statement is made with some jest, but there is truth in those words, too.

This is why open channels of communication between parents and teachers are essential.

6. I always think that a phone call to a teacher is always better than a letter to some arbitrary expert. If a parent wants to affect immediate change for their child, a conversation with the teacher is the best route to take.

As for the response made by Stallings to this question (and my own advice), here is what I think:

Positive reinforcement is an excellent way of promoting positive behavior, but Stallings' description of positive reinforcement as "little trinkets, tchotchkes, gewgaws, kickshaws, and surees" is either a misunderstanding or a mischaracterization of the many ways that positive reinforcement can operate.

Positive reinforcement - absent any extrinsic, physical rewards - is extremely effective when the teacher-student relationship is strong. When my students know that I love them and want nothing but the best for them, a positive word of encouragement can mean the world to them. When students want to please or impress their teacher, positive reinforcements in the form of verbal recognition for a job well done are incredibly powerful at any age.

But we all know this. When your spouse tells an audience that she is proud of you, or your best friend says that he respects the hell out of you, or a colleague tells you that your support has changed her life, these words stay with us forever. Similarly, when I tell a student that I am proud of they way she persisted through a math problem or impressed with the way he compromised with a classmate, those positive words increase the likelihood that those behaviors will be repeated again.

This is what effective positive reinforcement looks like, but it begins with the teacher-student relationship. If a teacher has not taken the time to forge a bond with the child, positive reinforcement is decidedly less effective.

This is not to say that there is no role for consequences. I am considered the master of consequences in many teaching circles, often finding punishments that are specific, appropriate, and astonishing to students. Teachers come to me looking for consequence suggestions. Recently a student who did not complete her homework was required to write a list of 50 complimentary statements about her sister (who she claims to despise) in cursive. This consequence accomplished several goals:

- It forced the student to spend time that should have been spent on homework.

- It re-established equity between the student and her classmates, who had taken the time to complete their assignment.

- It gave the student the opportunity to practice her cursive writing and grammar.

- It demanded a certain level of creativity.

- It hurt. She hated writing the list, though when she was done at the end of the week, she laughed with her friends about the list.

- Her parents approved of the consequence. They thought it was both amusing and appropriately time consuming.

For this particular student, writing about the intelligence and beauty of her sister in cursive was an excellent consequence.

For another student, taking away a recess might be appropriate. While I use this particular consequence extremely rarely, it can be highly effective in changing the behavior of specific students.

Regardless of my consequence choice, it is always attached to a conversation about the rationale behind my decision and strategies for avoiding the situation in the future.

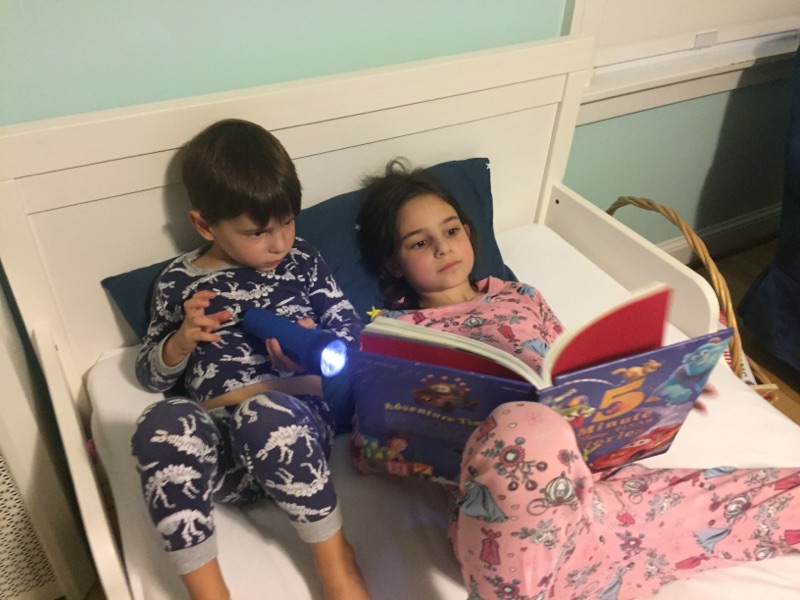

This doesn't mean that a student won't cry when assigned a consequence. When my daughter received her first "ticket" from a teacher in kindergarten, she had tears in her eyes when she presented it to us. While the tears broke my heart, she also knew exactly what she did wrong and how to correct it next time.

The teacher had done his job well. Sometimes kids cry. Sometimes adults cry. It's a simple fact of life. I hugged her, kissed her, and we moved on.

What I didn't like about Stalling's response was the first few sentences of his answer:

He was in tears for having to miss recess? Ah, sweet innocence of youth. Let’s hope he never gets a really tough consequence. Or a boss. Or a job.

I don’t see what the teacher did as either horrible or tear-inducing. My advice would be to have a conversation with your third-grader on the topic of “coping skills.” Because if being kept out of recess has destroyed his love for school, I shudder to think what’s in store when he gets to algebra.

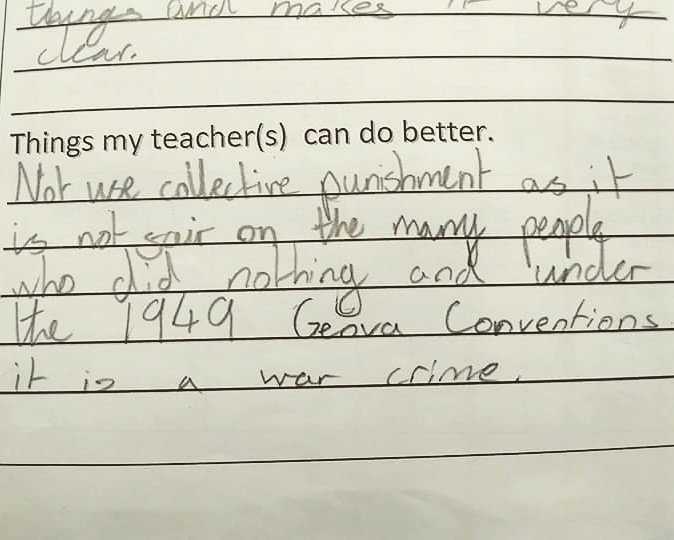

While his advice is solid if grossly incomplete (talk to the child about coping skills), the cavalier attitude toward an emotionally charged situation between a parent and a child serves no purpose here and fails to acknowledge the reality of childhood:

To an eight year-old child, the loss of a recess might be a really tough consequence. It might be the toughest consequence that this child has ever received. While it might still be an appropriate consequence (I don' know enough about the child's history to determine this), we can't simply dismiss the child's feelings as silly or inconsequential. "I shudder to think what's in store when he gets to algebra" is a lousy thing to say to a parent who is worried about her child and a lousy thing to think about a child who has just experienced something frightening and unprecedented, albeit perhaps deserved.

As a student, being sent to the principal's office was not a big deal for me. There were times when I looked forward to the verbal exchange that I was going to have with my principal.

But I know I had classmates who viewed a trip to the principal's office as the worst thing that could possible happen to them, and this was a perfectly valid feeling given their history and disposition.

Human beings react to the same circumstances in wildly different ways depending on their previous experiences and a variety of other factors. To think that an eight year-old should have a stiff upper lip when faced with a punishment lacks empathy and decency.

I would tell the parent who asked this question to speak to the teacher. I would advise that she approach the conversation as a partner in the education of her child with the assumption that the teacher wants nothing but the best for her son. In 99% of the cases this will be true.

A less combative approach is the best way to proceed and will likely produce the best result possible.