The New York Times reports that Pulitzer Prize winning author Junot Diaz is a former Dungeons & Dragons player.

So too was Pulitzer Prize winning playwright and screenwriter David Lindsay-Abaire.

Many more.

The league of ex-gamer writers also includes the “weird fiction” author China Miéville (“The City & the City”); Brent Hartinger (author of “Geography Club,” a novel about gay and bisexual teenagers); the sci-fi and young adult author Cory Doctorow; the poet and fiction writer Sherman Alexie; the comedian Stephen Colbert; George R. R. Martin, author of the “A Song of Ice and Fire” series (who still enjoys role-playing games). Others who have been influenced are television and film storytellers and entertainers like Robin Williams, Matt Groening (“The Simpsons”), Dan Harmon (“Community”) and Chris Weitz (“American Pie”).

It’s an impressive but certainly not exhaustive list.

Not exhaustive, for certain, because it does not include me. I am also a former Dungeons & Dragons player.

In fact, D&D brought me back to writing and saved my writing career.

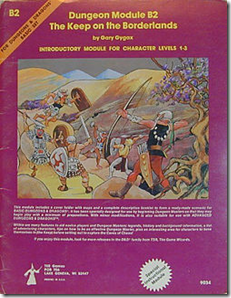

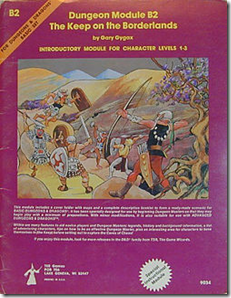

I first started playing Dungeons & Dragons in middle school, when a friend introduced me to the game. I rolled some dice, created a character, and played The Keep on the Borderlands, an adventure that I can still remember to this day. I fell in love with the game immediately, and before long, I had stopped playing and had graduated to Dungeon Master, the leader of the adventure. The arbiter of the rules, the invisible hand of fate, but most important, the storyteller. I began by using pre-purchased Dungeons & Dragons adventures (called modules) but was soon writing my own adventures for my players.

In many ways, I was writing stories for the first time.

I played D&D throughout much of my childhood, becoming a scholar of the game. When cars, girls, and high school sports injected themselves into my life, Dungeons & Dragons was pushed aside. I briefly played again after high school with friends who were attending college. Then my manuals, modules, and multisided dice were packed away and moved to the basement, never to be seen again.

Or so I thought.

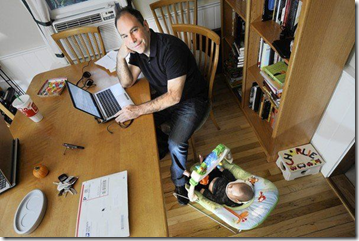

Fast forward about 12 years. It’s 2002. I’ve graduated from Trinity College with a degree in English and creative writing, and for the last five years, I have been trying and failing to write my first novel. Nothing I seem to do works. Nothing I write makes me happy. After many failed attempts, I have given up on my dream. I’ve come to the realization that as much as I want to be an author, even I don’t like the things I write.

I quit. I decide that I will never be an author.

Then I get a call from my friend, Shep, a former Dungeons & Dragons player in his childhood. He has gathered some of our friends (also former players) and wants to try playing the game again. He asks me to join the group.

At this point in my life, I am single and hoping to find the right girl, and I don’t see Dungeons & Dragons as the path to romance, so I decline.

He calls back a few days later. He tells me that I don’t need to play. “Just write our adventures. Maybe serve as Dungeon Master, if you want, but at least write some adventures for us.”

I suddenly have an audience for my writing. People want to read the words that I write. People are asking to read the words that I write. Something stirs inside me. I say yes.

I write D&D adventures for my friends for more than a year, and yes, I am convinced to occasionally reprise my role as Dungeon Master, too. I write hundreds of pages of Dungeons & Dragons adventures, and as I do, the writer in me awakens. I start to feel good about writing again. I start to wonder if I can still be the writer that I dreamed of being when I was in high school.

It’s an exciting time in my life.

About a year after my return to Dungeons & Dragons, I call Shep. I tell him that I can’t write D&D adventures anymore. I tell him that I need to try writing a novel again. I tell him that I feel that pull toward the page that I have not felt in so long.

He understands. He offers to read whatever I write. Shep becomes my first reader. He remains an early reader and one of the most important readers of my work to this day.

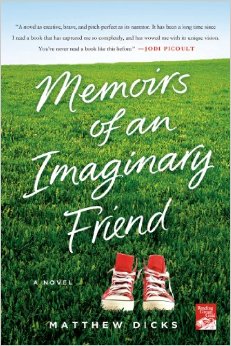

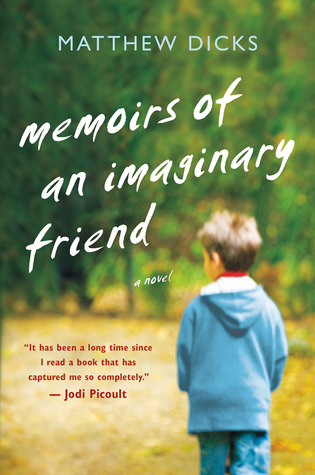

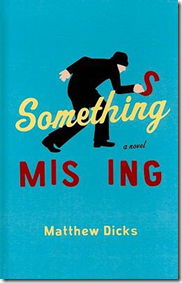

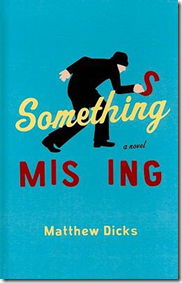

I start writing Something Missing in February of 2005. I finish writing it in June of 2007. It publishes in 2009.

I have made my childhood dream come true. My writing career has been launched. I am an author.

Would I be writing today if it hadn’t been for Dungeons & Dragons? I would like to think that I would’ve eventually returned to the page, but I’m not sure.

Maybe not.

A friend in middle school introduces me to the game.

More than twenty years later another friend brings me back to the game.

I find my chops. I rediscover my love for writing. I start the novel that launches my career.

Take away either one of these friends and I shudder to think about what might have happened to my dream/

Take away Dungeons & Dragons and I wonder if I would be sitting here today, writing these words.

Maybe not.