I know a handful of college professors personally. I know a handful more via Facebook and Twitter. I have known many, many more throughout the years. Right around this time of the year, the discussions about their fabled syllabi begin to appear, both in real life and on social media.

Their comments can usually be boiled down into the following statements:

- I am working on my syllabus.

- I feel angst about my syllabus.

- The work that I’m doing on my syllabus is complex and time consuming.

- I am proud of the work that I have done on my syllabus.

As a teacher, I find this never-ending conversation about syllabi both amusing and disturbing.

Let’s start off with the dirty little secret of higher education:

Professors are not teachers. The great majority of them have almost no formal training and have never studied the art and science of teaching. They are experts in their specific fields of study, and if their students are lucky, they have received a modicum of training from the college or university where they teach (usually a week or two before the semester begins), but for the most part, they do not have any actual teaching certification, scholarship, or meaningful training.

This is not to say that their instruction is ineffective.

However, in many cases, it is highly ineffective. I have attended classes at six different institutions of higher learning, and I have met many professors who are experts in their field of study and utterly inept in the classroom.

Thankfully, I have also been taught by professors who are incredible teachers, too. For the most part, I suspect that these people possessed many of the innate qualities of an excellent teachers long before they entered the classroom. I also suspect that these professors have chosen to study the art and science of teaching with the same vigilance and rigor as they study in their field of expertise.

These people are teachers disguised as professors. They are highly effective, oftentimes inspiring, and sometimes life changing.

Unfortunately, they are too few in number.

Which bring me back to the syllabus:

The carefully designed plan for the entire semester. The source of both angst and pride of so many professors and students.

Also one of the most disastrous and ridiculous documents in the field of education.

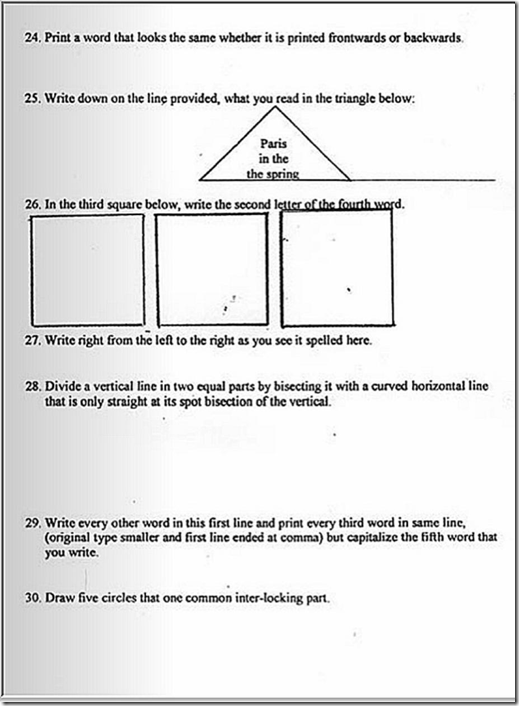

The syllabus represents a professors plan for instruction for the course of approximately four months. It is disseminated to students at the beginning of the semester, and in most cases, it is adhered with rigor and fidelity. Due dates are predetermined and enforced. Readings are assigned and expected to be completed by the date indicated. Lectures and coursework is paced in accordance with the schedule set forth. Everything that students will be doing over the course of the semester is listed in clear, explicit language.

Ask a teacher to teach using a similar plan and he or she would laugh you right out of the classroom.

At its most fundamental level, teaching is a process that requires engaging instruction, ongoing assessment, constant differentiation, and relentless adjustment.

A syllabus is the antithesis of this. It represents uniformity. It dictates a predetermined pathway for instruction. It sets expectations that apply to all students, regardless of talent or ability. It predetermines precisely how long a group of learners will pursue a particular topic.

This is, of course, ludicrous. This is not teaching.

An example:

My hope may be to finish reading Macbeth with my fifth grade students by September 28. That is my plan, and I have communicated it to them (though being fifth graders, I’m sure that most don’t remember this). But if my students don’t understand certain concepts in the play or are incredibly enthusiastic about the text or ask unexpected and surprising questions or despise Lady Macbeth with every fiber of their being, that September 28 deadline could easily drift forward or backward.

I will assess understanding and enthusiasm and adjust accordingly.

This is the essence of good teaching.

I will also adjust my instruction based upon my students’ individual needs. I will seek to understand those differing levels of ability and differentiate instruction based upon my students’ specific skill levels.

Nothing is static. There is no four month plan, because there can be no four month plan. I work with human beings. Not widgets.

My plan is to study four Shakespearean plays before our winter break. That number may increase or decrease based upon any number of factors.

My students may be so thoroughly enthralled with tragedies that I decide to skip the comedies entirely. Or at least delay them until the spring.

A graphic novel of Macbeth may be released that I decide to add to our study. Or a film. Or a play at a local theater. Or a student-created puppet show.

Any number of factors will alter content.

This is what teaching is all about. Engaging instruction and relentless adjustment.

But this is how many, and perhaps most, college classes are typically taught. The syllabus determines the what and when.

In a college classroom, assessment rarely drives instruction. The syllabus drives instruction. Assessment is used for determining grades. It does not determine which students require additional instruction. It does not signal to professors that their students require additional time or increased levels of challenge in order to achieve their greatest academic potential.

“Greatest academic potential” is a state that all teachers seek for their students. But in order to achieve this state (or even strive towards it), a teacher must constantly monitor, assess, adjust, and differentiate.

I have almost never seen this process take place in a college classroom.

Rarely is work at a college level differentiated. Despite obvious differences in the backgrounds and abilities of students, instruction is delivered to all students at the same time in the same way.

In college, differentiation is not done in the classroom. It is not handled through instruction. It is parceled out in 15-30 minute chunks known as office hours.

To an actual teacher, this is insanity.

I believe that it’s this relentless march though the syllabus that has led to the rise of online learning and MOOCs. Rather than acting as teachers, professors have presented themselves as content delivery systems. They set forth a plan and adhere to it, lecturing, assigning grades, and marching through their semester regardless of circumstance.

You will read about Subject X before Monday. I will lecture about Subject X on Monday. We will engage in a class discussion. You will write a paper on Subject X, which is due the following Monday. I will assign you a numerical score based upon your adherence to a rubric that I have determined.

What about the student who struggled with the reading?

What about the student who was not challenged by the reading?

What about the class who does not find Subject X nearly as engrossing as you do?

What about the class that wants to spend another week discussing Subject X?

As a teacher and a former college student, I would like to see the college syllabus become more of an approximate plan for the semester, with fairly rigid timelines in place only in two week increments.

“Here is what we will be doing this week and next. It includes the readings and assignments. We’ll see how it goes. Then we’ll figure out the next two weeks. Because we are learners. Not robots.”

Teachers do not speak of their curriculum or lesson plans with nearly the same consternation or affection as a college professor does his or her syllabus because the teacher knows that curriculum and lesson plans are great until class begins. Then the real teaching starts.

As German general Helmuth Von Moltke said:

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

A majority of college professors do not subscribe to this belief. They encounter the enemy (their students) and march forward, regardless of obstacle or resistance.

Follow the syllabus. Administer the tests. Finish the semester. Ignore the wounded who litter the battlefield.

This is not teaching. It’s content delivery.

It’s a damn shame.